A large bucket of popcorn. An extra large blue-and-red Borg smushed-together ICEE. And an extra indulgence—the holy chicken tendie. I am 34 years old and I am ready to watch the Superman movie.

As a kid, I was a fan of the corny Christopher Reeve films. As my tastes became more refined (read: more annoying), I was instructed to only respect the Richard Donner cut of Superman II. Gunn admittedly cribs from the Reeve style, but not in a way that feels tired or inauthentic—unlike the short-lived and deeply strange 2006 Superman Returns.

In Lois Lane’s apartment, Superman says it plainly. He’s not hovering or giving a speech. He’s just standing there, in a tight button-down shirt, looking gallingly swole, and he says: “I’m just trying to do good.”

It’s after the fictional Boravia tried to roll tanks into neighboring, undeniably Arab-coded Jarhanpur, but Superman stopped them. The world turned to him to explain his “intervention.” The backlash was fast and, like everything, online. The real villain these days is the internet, isn’t it folks? In that moment, he tells Lois he’s not trying to be a god, or a symbol, or an icon. He’s just trying! And not everyone (the war machine, the bad guys, angry uncles) wants him to.

His exasperation felt familiar. Maybe because I’ve heard it from organizers, from friends, from myself—after a long week of fighting a system that rewards nothing but compliance. You do the right thing, and the knives come out anyway. Speak up, and people who pretend to be allies call you a traitor. Try to be decent, and someone always asks, “What’s your angle?”

I liked the movie more than I thought I would; that’s the simple review. I expected another washed-out nostalgia trip, a post-Snyder rehab project. But James Gunn’s corniness works—because as comic fans know, there is no one cornier than Clark Kent. He is the blueprint for sincerity.

Still, even as I write this, I can feel the resentment rising—for myself, for any of us—for trying to extrapolate meaning from a franchise product. For parsing a studio tentpole like it’s a dispatch from the front; for making a $225 million corporate product mean something. Not because it’s necessarily wrong, but because it’s stupid. It’s cultural gruel dressed as myth.

We know what American culture does. We’ve seen the migraine-inducing discourse cycles. Is Superman an immigrant? That’s it. That’s the conversation. An alien born on a planet called Krypton who crash-landed in Kansas—should we let him vote? Is he WOKE now? Does he love America? Can we give him a moment with a random guy who gets a callback later?

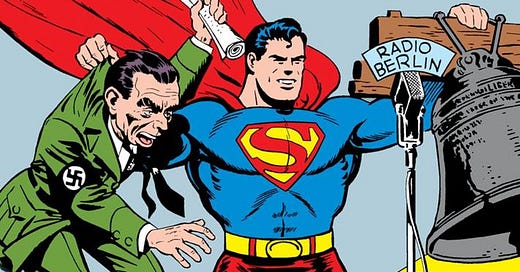

Dean Cain, the Superman I grew up watching on Lois & Clark (which I loved, no notes, I was seven) now laments that calling Superman an immigrant is “too political,” or something. A literal alien from outer space—god forbid American propaganda be attached to a famously good, albeit entirely fictional, immigrant. And written, by the way, by a couple of Jews: Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Back then, the Third Reich didn’t like Superman either.

When Superman comics showed him punching Hitler and tearing through Nazi fortifications, the Nazis responded in their official newspaper Das Schwarze Korps by denouncing Siegel personally, mocking his Jewish identity, and calling him a “Colorado beetle”—a pest. They were so mad at a cartoon character they launched a propaganda attack on the creator. So it’s true that it was never just entertainment.

But I’d say, in 2025, we’re a bit culturally saturated with this kind of thing now. Superman-esque variants of all shapes and sizes. It’s all a bit absurd. But still, there I was, slurping my ICEE, nodding along when Superman said he was just trying to do good. And I believed him. My beautiful big boy in underwear.

There’s an unmistakable nod to real-world geopolitics in the Boravia storyline—Boravia being a fictional stand-in for… what? Israel? Ukraine? A little of both? The script leans in just enough to get the nerds fighting online. America’s “most important ally.” A nation under constant threat. Jarhanpur, meanwhile, is a site of humanitarian crisis the world mostly ignores. Superman steps in to prevent—well, he says “death.” Some might say “genocide,” but the film doesn’t use that language.

Boravia’s dictator is cartoonishly evil, though that’s harder to laugh at when you live in a world with real-life villains like Netanyahu. I could see someone saying the portrayal leans antisemitic—but it’s also funny. The character has the same energy as Bibi himself, whose own evil feels subtle in the same way J.K. Rowling is racist. (Reminder: her Asian character is named Cho Chang, and one of the only Black characters is named Shacklebolt.)

Maybe the movie gets away with it because it isn’t trying to be edgy, it’s trying to be earnest. Superman isn’t conflicted about saving people, he’s conflicted about being seen saving people. He’s afraid his goodness won’t be enough, or worse, that it’ll be used against him.

And that felt right. Because we’re in a moment where doing actual good gets you arrested, doxxed, fired, and endlessly discredited.

I was thinking about this when I went to the launch party for the newest issue of Lux magazine, the Brooklyn-based socialist feminist zine. Yes, really. No, there was not a DJ this time.

My friend Calla Walsh was there. She’d just had her case dismissed after being arrested last November for attacking Elbit Systems, the Israeli weapons manufacturer. She was nineteen at the time. We talked briefly about George Jackson, about jail, about strategy. The mood in the bar was that everyone was tired. Tired of being nice, and even more tired of being called dangerous simply for not wanting to die quietly.

That’s the subtext of everything now, isn’t it? Everyone feels it. That the organizing, the petitions, the marches—they mattered, yes—but something else is required now. Something scarier and lonelier.

What do you do when “trying to be good” isn’t enough?

Even Superman is exhausted. The fictional most powerful man on Earth has to explain himself to people with microphones and checkbooks. But it’s hard to be good when goodness is treated like a threat.

In some ways, the conceit itself is deeply liberal without even realizing it. Presumably, Superman could free the oppressed classes all over the world, no? What’s stopping him? Democracy? The rule of law? Are we really meant to believe that a man who can fly and lift tanks is constrained by congressional procedure?

I don’t mean to be annoying, look, I had fun. I bought it. I teared up at sweet Ma and Pa Kent fawning over their adopted son, at Pa giving his sweet boy an inspired bit of wisdom. I just mean to say, even our fantasies have been invaded by a kind of liberal defeatism. A cap on the horizon for what “good” men can do. We’re so spiritually colonized by paperwork and process that we can’t even imagine freedom without bureaucratic red tape. In the most fantastical version of our world, we’re still being murdered by committee.

But forget Superman. That guy wears his underwear outside his pants.

The real people are out there showing up. Cheryl Rivera, one of the Lux editors, who built Another World, a community space in Brooklyn rooted in youth education and Marxist solidarity. Calla, who faced years in prison for attacking a direct link to the genocide machine, walked out of jail and got right back to work. People still driving their neighbors to court or posting their Venmos for bail funds and mutual aid. Not because they want to be heroes, but because they’re trying to be good. No cinematic redemption arc required.

There’s a reason the state hates Superman, and it’s not because he’s strong. It’s because he acts without permission. In doing so, he makes their power look unnecessary. And it is.

It’s the same reason they hate the ones who chain themselves to university gates, or attack weapons manufacturers, or hand out sandwiches and hot meals with organizations like Food Not Bombs and get ticketed by the cops for it.

What does it really cost to do good?

The next stage will be harder. It may ask more than we think we can give. But when it comes—and it’s coming—we won’t be able to say we didn’t know.

It feels silly to try and interpret what this film means. It’s a superhero blockbuster. Are things that dire? Why the fuck are we looking for meaning here? Resist the urge to say, Wow! A secret message to us! Thank you, Mr. James Gunn, sir! I hope Brainiac is in the next one!

It feels almost insulting to be so flip about it. The Nakba—the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians—happened in 1948. Since October 2023, it’s not even possible for health organizations to estimate the number killed by Israel’s military. We can only speculate that when the dust settles, the number will be many magnitudes greater than the figures most currently reported, which are fifty thousand plus vaporized. The idea that there’s some grand importance to the narrative in this film—which does feel of the moment—feels entirely too optimistic, and borderline revisionist.

Qasem Soleimani, the Iranian general, was assassinated by a U.S. drone strike in 2020. After his death, an Iranian cleric joked that the Iranians wouldn’t be able to strike back in kind—because all America had were fictional heroes like Spider-Man and SpongeBob. All our symbols are flattened, our courage outsourced to myth.

I want to feel good at the movies, baby. And I do. But it’s a fairy tale, is the problem.

Is this Huxley’s soma? Our beautiful sedative?

Gimme that slush and those tendies; I’m ready to save the world in my mind palace.

I’ve developed a personal bond to the CGI dog. Lois Lane is here.

Up, up and away.

Love the shoutout for Another World! Cheryl is the best. If anyone in NYC wants to check out a really dope community space, I highly recommend Another World. A/C, free wifi, free snacks, and cool events like political education. Also def donate if you’re able so you can help sustain the space!

As a lifelong comic book fan, I feel like this is where I’m at in the moment as well. I love comics and heroes because they find ways to endlessly inspire and to challenge what the meaning of being good is in modern life (when they’re written correctly). But when that inspiration does not spur us to act righteously in our own lives, it all just feels so…hollow. Alan Moore famously hates superheroes now because of how it infantilizes its readers and allows them to never grow or take on the challenges of their own life, and as much as I want to disagree with him…is he really wrong? Thank you for vocalizing partially how I feel as a leftist fan of superheroics, really well written and thought provoking as always