"Battles are won in the hearts of men."

— Vince Lombardi

There’s a particular kind of nostalgia that doesn’t smooth over the rough edges of memory but embraces them, the way scars become part of the body’s story. That’s what I think as I try to conjure the smell of the library at the Catholic all-boys school I attended. I certainly was not part of the typical pipeline for it: my father is Jewish and I went to public school for most of my life. When my two closest childhood friends were suddenly going, now, according to my single mom, I was too. This was, in my opinion, a masked revenge against my secular father. It was successful as he has remained annoyed by it ever since.

There is a smell to the library of stuffy private schools that I suspect is similar everywhere. The carpet is too old. When the heat is turned up too high in the winter, as there is no official temperature setting on the outdated thermostat, it feels as if you are breathing in the material itself, choking on it. After about fifteen minutes you get used to it.

They have reverted to cleaning it once, every summer, with these hulking machines with large metal round bottoms that must weigh sixty or seventy pounds. The monstrosities shoot out liquid soap when you pull the trigger on the handle that quickly turns to foam under the spinning round bottom. The key is to balance the handle off of your hip, to avoid the entire thing tearing off and spinning out. This will inevitably happen, and when it does, the supervising janitor will scream expletives in Spanish.

I spent every summer of my high school years manning these machines, cleaning the classrooms and finally and with great fanfare, the library, for seven dollars and twenty-five cents per hour. Fifty-eight dollars a day. For the ten weeks of summer, this ended in a grand total of two thousand, nine hundred dollars. I have been paid more for making a single TikTok video. If I reflect on this for too long, my mood becomes remarkably dark.

It's been some time since I’ve considered my high school experience, in no small part because it was often quite torturous and difficult, so much so that I’d rather not consider it. A friend I still know today, a freshman who sat with a group of us at lunch for my entire junior year, was relentlessly bullied for being somewhat effeminate. He would years later come out as gay, obviously.

I was also one of his bullies, and personally made sure everyone around us knew that his middle name was “Gagen.” This name stuck to him for all four years. Unfortunate, but your name really cannot be “Gagen” in an all-boys Catholic school. Fortunately, he was, for lack of a better term, extremely cunty and would mine the trauma he experienced for several years as a talented playwright.

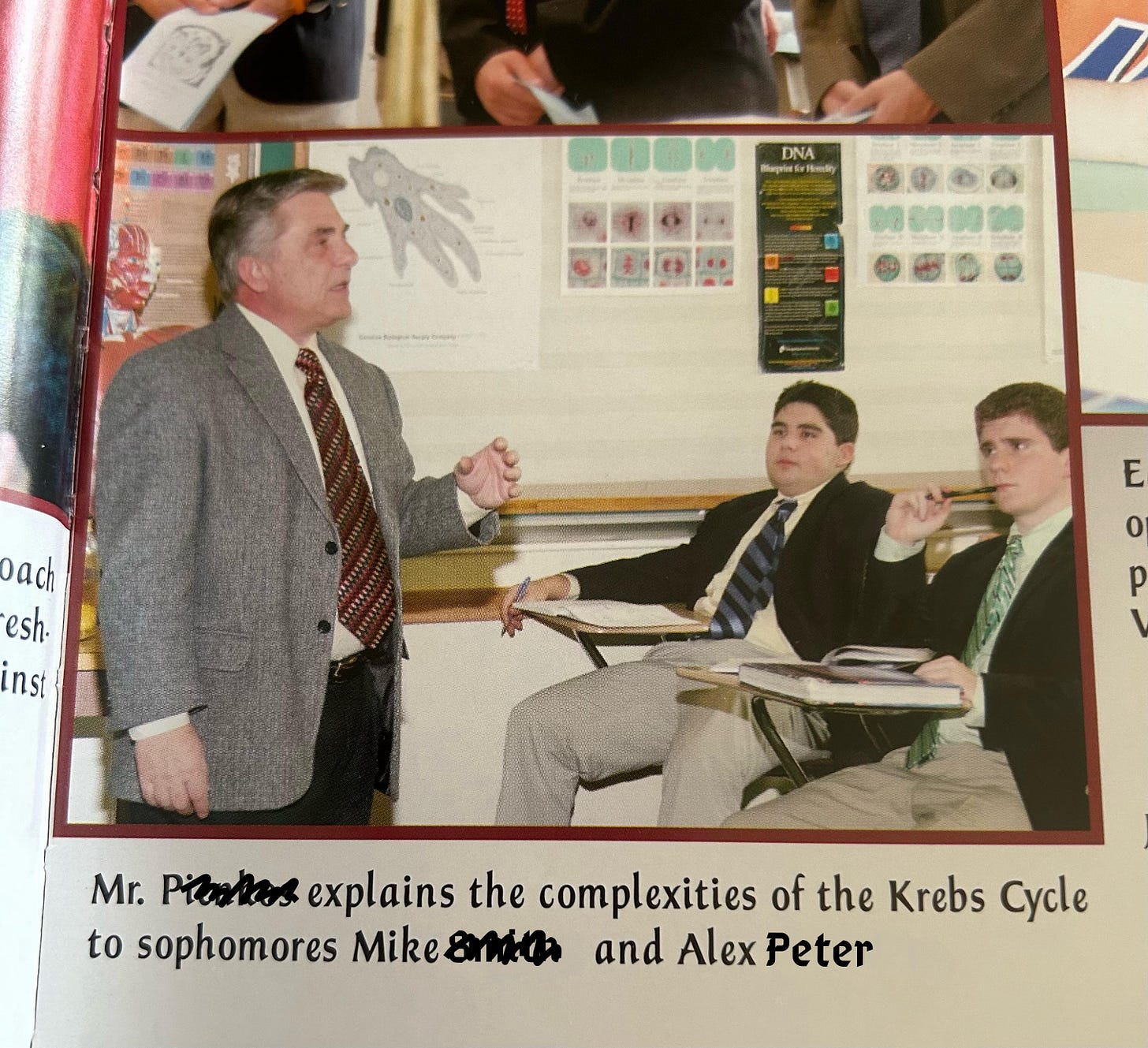

Pictured: Your high school bully who looks 35 years old at 17

I should also note that if someone else was getting bullied, you were safe, at least temporarily. This often proved to be a foolish outlook, which you would realize quickly when the unfortunate lens of hatred was trained on you. In those moments, it was best to play dead and accept your fate or quickly shift attention to another unfortunate soul. Now when I see Gagen, who also lives in Harlem and frequents the same coffee shop, he hugs me. “My bully is here!” he exclaims. It is, as far as I can tell, one of his favorite things to do.

I cannot express enough how brutal of an environment it could be. There was a boy who ejaculated in his pants his freshman year while dancing with a girl at a Friday night dance, where girls from our “sister school” were bussed over. For all four years, he was referred to as the unceremonious “Jizzum.” Even teachers called him this. I once was jumped in the boy’s bathroom without warning or reason, by two boys two years my senior who would later be expelled for possessing cocaine. One of our classmates, known for being a member of the after-school work-study cleaning crew, took his own life our junior year. I ate breakfast with him the morning he died. At his funeral, the head priest of the school, who would later flee the United States for the Holy See because of allegations of improper conduct with students, stated that he was “cleaning heaven.” The audience groaned.

I barely made it out of there myself, nearly getting expelled at the end of my freshman year for repeated transgressions that resulted in, from what I can recall, at least 30 separate incidences of after school detention where we were forced to write Vince Lombardi quotes on lined paper for an hour. The same happened to one of my closest friends the next year. We both made it out by the skin of our teeth. Two years ago, I was the best man at his wedding.

All these memories are percolating after a fateful rewatch of The Dead Poets Society, a mawkish but ultimately heartfelt film about an all-boys boarding school in Vermont – though it could be set anywhere in the northeast. The film is such a classic that it’s hard to sort out what are now overused tropes from what really works. The teacher who is finally going to reach these damn kids, the stifling rigor of prep school environment with its disapproving fathers, the extremely gay undertones. But even so, it remains a lovely film.

I find myself quite embarrassingly weeping almost immediately at the opening scene. It depicts a church mass with the new students, the youngest boys, and older ones soon off to college in a cavernous basement church that is likely underneath one of the large, gothic styled buildings of the campus. I recognize these boys immediately as I was one of them. I had the same ties, the scratchy herringbone jackets, the over-starched white collars. I sat in the very same masses and listened to the same droning homilies trying to make my friends laugh while avoiding detection by one of the Marianist brothers. Though I often found myself rolling my eyes, still I absorbed the words of hope and promise that imagined a brighter and more vibrant future full of possibility.

I am moved to tears by the distance I feel from that boy in those pews, as now nearly twenty years have passed since I first entered those doors. While I do not feel old, I recognize that I now have more in common with Williams, the 38 or 39-year-old English teacher who has returned to his alma mater to try and impart his wisdom on these young men.

I am reminded of one of the Marianist priests, Father Ernest, who I realize after searching has sadly passed away in 2020. Father Ernest was a strange character, in service of the Marianist brotherhood and my high school for fifty years and always full of at times profound and other times incoherent and bizarre wisdom. “Dear Boys,” was Father Ernest’s catchphrase, which he would utter before imparting some fact or figure or lesson about life.

When I was sixteen years old, he stood in as a substitute teacher in one of my classes and on the old projector whirred up Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, explaining it as a necessary piece of history for all young men to understand. “Dear Boys,” he interjected often, explaining scenes in detail and getting some clear enjoyment out of showing us the famous scene of Antonius Block playing chess against Death. His eyes went back and forth from the screen to us. “Watch closely, dear boys, watch closely,” his eyes were wide and he smirked mischievously. We laughed.

Pictured: The Seventh Seal featuring Swedish Chef

I often consider myself to be romanticizing this time in my life but the more I reflect, I believe much of it is not, in actuality, a romanticization. I remember the anger I experienced from being treated badly, I remember the immense social pressures and backwards political priorities of a pious group of religiously trained and professionally poor men.

The Marianist brothers wear wedding bands because they are “married” to the Church, or Christ, or the Virgin Mother. Their devotion was sincere and not something I ever doubted, but often marked by what I now understand as a kind of ignorance, or lack of care, for reality. It was, in my estimation, at base a sympathy for the poor, not an empathy. While praying for the poor, they were hosting golf tournaments for some of the wealthiest people in New York. To raise money, of course, for the dear boys.

Despite what is now close to an entire century of pouring out these “good” men, its alumni, men like Bill O’Reilly, have done little to improve the realities of the world and in fact have often contributed to its horrors. The brothers’ ignorance, a kind of blindness, seeped into an environment that allowed dear boys to become awful men.

There was still a kind of beauty to it all, even as brutal as it could be. The messages were often correct: the need to be men of service, the idea of brotherhood. The idea of “The [School] Man,” drilled into our heads incessantly. The [School] man does the right thing, at the right time, because it is the right thing to do, regardless of who is watching.

The rituals of an environment centered around worship brought a sense of quietness, a reflectiveness, a calm that I struggle to find even now. But what was uglier in me became something lovely as I grew and changed and learned, and what was lovely in some of my classmates, my brothers, who I loved, grew into something ugly and hateful, like milk beginning to sour.

I think back to those dear boys. The boys I watched over the years become victims of right-wing conspiracy thinking, or gobbled up in a haze of bigotry, or simply the relentless pursuit of self-actualization by creating the largest pile of money possible.

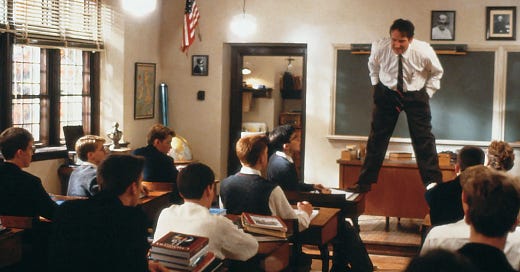

“Thank you, boys,” are the final words of Dead Poets Society. Robin Williams’ Mr. Keating says it as he leaves the classroom for the final time after – spoiler – he has been removed from the school for being the scapegoat for a student’s death. He thanks them for standing up for him. They literally stand on their desks, reciting Walt Whitman’s O Captain! My Captain! It does not escape me that these boys, who form the secret club known as The Dead Poets Society, are also standing up against a thoughtless and unfeeling school administration that churns out thoughtless and unfeeling young men.

Now I sit, an older man, looking back at the boys we were. Thinking of them and how we each got to where we are. I feel a deep sense of sadness and loss. I wish those boys well. They made me, for better and worse, and I carry them with me still. My dear boys.

I went to a Jesuit all-boys high school. Every year the contradiction of that place seeps deeper into my brain.

On the one hand - we had a school counselor who would recite the Lord's Prayer over the loudspeaker with gender-swapped pronouns ("Our Mother, who art in Heaven") ; my junior year theology teacher vehemently defended gay marriage and the legitimacy of LGBT personhood generally; one of the priests would break the brittle childhood faith of boys every year by showing there was no archeological evidence of the Israelite enslavement in Egypt nor the subsequent Exodus; other priests introduced me to liberation theology and a solidarity-centered, leftist social justice framework that would chart a course for the rest of my life.

On the other hand. Drunk moms stuffing cash tips into the waistbands of the popular, good-looking boys volunteering at the annual Crab Feed. The whistles and catcall at the fashion show fundraiser with our sister all-girls' schools. A Board Member (and local Coca-Cola bottler executive?) intervening personally to ridicule me for writing an article about Coca-Cola's alliance w/ death squads in Colombia to crush labor organizing. A complex web of sexual impropriety between one of the deans and several of the female faculty that resulted in his firing and, predictably, a petition for his reinstatement by the water polo alumni.

There was a beautiful heart to that place that genuinely sought to produce "Men for Others", but there was also a miasma of nouveau-riche suburban depravity and political conservatism that just *hung* on it like rotten moss.

Idk what the point of this comment is other than to say you evoked a particular, powerful mood Lolo! Wonderful writing per usual.

Happy Sunday, Happy Reading! 🙏🏼❤️