This past week, two Israeli diplomats were assassinated. Both of them, people said, were just kids. In the prime of their lives. They had family and friends. Perhaps most tragically, the pair were partners, soon to be engaged. They weren’t Netanyahu. They didn’t run the army. They worked in policy. And maybe in another world, either would’ve done something else entirely.

Yaron Lischinsky was one of two killed. He grew up in Germany, moved to Israel at sixteen, and served in the IDF. Friends have since described him as thoughtful, faithful, and someone who liked asking hard questions. He earned a master’s in diplomacy and worked in policy for the Israeli government. On social media, he questioned reports that Israel bombed ambulances. He called UN statements about starving children in Gaza a “blood libel.” He publicly supported the Israeli military throughout its siege and ongoing genocide of Gaza.

If you’re not someone who keeps up with it, it’s literally impossible to measure how many have been killed in Gaza. Conservative estimates leave it at around six figures – last updated by medical professionals in June of last year. Whenever the dust finally settles, it would not surprise me if the total reaches half a million killed. Since March of this year, by the IDF’s own admission, 80% of those killed have been civilians.

The shooter was explicit in his manifesto that his action was about the genocide in Palestine. He flew from where he lived, in Chicago, to Washington D.C., to an annual “Young Diplomats Event,” something hardly articulated as such by the media and politicians. The event has been almost exclusively framed as a “Jewish event” at a “Jewish museum.” But if the goal were simply antisemitic violence, wouldn’t the shooter have targeted one of the many synagogues in Chicago—where he lived—instead of flying across the country to a specific political gathering in D.C.?

On Friday, the Israeli Ambassador to the United States said, “This is done in the name of a political agenda to eradicate the state of Israel.” So yes, it was a political act. Part of Zionism’s goal is to conflate Zionism with Judaism—to make the colonial project inescapably tied to the religion, for the very purpose of roping in all Jews to Israel’s woes, even the millions born in the United States, even those who openly oppose the occupation. That conflation doesn’t just flatten political discourse; it makes the world more dangerous for Jews. That’s part of the point: to make people feel there is no safe alternative but Israel. My father grew up in Scarsdale and was jumped more than once for being Jewish. Antisemitism is real. I grew up hearing those stories. I believe them. Which is partly why I find this moment so twisted: the way genuine horror at antisemitism is often co-opted to silence people speaking out against genocide.

A former colleague—someone I’d been close with for years—saw a post I made, where I said the violence of Israel’s siege would inevitably lead to this kind of retaliatory violence. She called it “the most callous, cruel, and unfathomably antisemitic thing” I had ever said. I read her message again and again, trying to find the part where I’d denied her pain. I hadn’t. I just refused to deny someone else’s. But this is what happens when grief and propaganda get woven together: it becomes heresy to suggest cause and effect.

All this brings us to a harder question: who deserves to die? Where are moral lines drawn? What about your friend who works in finance, structuring securitizations, greasing the wheels of the same systems that hollow out neighborhoods and crush entire countries under debt? Are they just a bystander? What about the consultant who helps oil companies rebrand as “green?” The lawyer who makes sure it’s all technically legal?

Certainly some of us are more “culpable” than others. But who gets named as an accomplice, and who gets to just be a person at work?

And does anyone deserve to be executed for it?

The reality is: even if you believe the system is rigged—utterly corrupt, beyond reform—most people are not willing to become the executioner. Even the people who believe they know, who think they see it clearly. Who think, yes, this is wrong, immoral, unethical and fundamentally violent. They still go to work. They vote, maybe. Donate, sometimes. Post, read, share information, maybe even protest. But violence? That’s someone else’s job.

If you're “middle class,” or upwardly mobile enough where you’ve got just enough to lose, you’re kept comfortable enough not to risk it. The American duopoly knows this. It’s not stupid, the system is built for this. The culture gives everyone a dopamine drip: endless entertainment and infinite outrage while rents climb and choices shrink. If you fall behind, there’s no floor. You can go from Starbucks to a cell in two months. And right now, some of those cells are in El Salvador. Human beings—migrants, the undocumented, the unwanted—are being deported and dropped into mega-prisons with no trial, no due process, no exit plan. Hundreds to a cell, packed like livestock in a concrete box. People disappeared into the carceral machinery of someone else’s war on drugs, war on crime, war on “terror.”

But who made that deal possible? Who funds it? Who signs it into law? Who drafts the memo? Who makes the spreadsheets? Who builds the software?

And perhaps more importantly: who just watches it happen?

Is there a part of us—those of us who are comfortable—that’s scared by what this means? I don’t mean reactionary fear, I mean a quieter one. What if the moral debts come due? What if there is no safe distance from the violence we normalize, enable, outsource? People like to believe the world is unfair in a way that will never quite touch them. That someone else will be punished; someone else will die. But what if the bill doesn't care who you voted for? How nice you were? What if saying this isn’t my problem was always the problem?

Yaron Lischinsky was not a neutral person. He moved to Israel to serve in the IDF. He worked as a diplomat. His social media was full of genocidal language, not euphemisms or vague dog whistles. He celebrated the destruction of Gaza. He positioned himself and his life as part of the machine that made it happen. And yet the moment he was killed, the narrative was that he was innocent, a civilian, and a victim of terrorism and antisemitism.

Did he deserve to die? And if you say yes, what does that mean for the rest of us?

Who deserves to die?

It’s the kind of thought I pondered as a law student.

I went to one of the top programs in the country. At orientation, they told us we could change the world. By graduation, 85% had taken jobs at corporate firms. Sullivan & Cromwell. Cravath. Skadden. Firms that built careers defending oil giants, enabling coups, evicting tenants, and helping banks make money off war. And still, those lawyers are seen as respectable, maybe even admirable. In part it’s because they’re not the ones pulling the trigger, they’re just the ones writing the contract.

I remember an essay I wrote in my legal ethics class back in my final year. The whole premise of the course was that you serve the client; that’s your job. The core ethic was drilled into us: you fight for your client, not your cause. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that sometimes, “zealous advocacy” was simply a shield. A way to outsource your moral compass and pretend you’re not responsible for what your work enables.

In the essay, I compared certain lawyers to pill mill doctors in Kentucky; they were technically doing their jobs, sure, but funneling something toxic into the system, knowing exactly what they’re doing. It’s not just corporate attorneys helping Exxon or Lockheed Martin. It’s the ones who launder police misconduct through “qualified immunity” briefs. The ones who make entire careers out of eviction litigation, turning other people’s instability into their salary. It’s legal, and it’s deeply unethical.

The job, I argued then—and still believe now—isn’t just to serve the client. It’s to ask who benefits from your service, and what gets destroyed in the process.

Real life is messier than philosophical discussions in law school. People don’t always have the luxury of abstraction. In 1938, a 17-year-old Jewish refugee named Herschel Grynszpan walked into the German Embassy in Paris and shot a Nazi diplomat. His parents had just been deported to the Polish border, stateless and abandoned. Grynszpan, desperate and enraged, acted alone. But the Nazi regime seized the moment and turned it into propaganda. They used the assassination to justify Kristallnacht—a state-orchestrated pogrom that burned synagogues, destroyed homes, and killed hundreds of Jews across Germany and Austria. One teenager’s act became a pretext for nationwide terror.

It wasn’t just the violence, it was the story told about it. Grynszpan became a symbol of supposed Jewish aggression. The real machinery of genocide, already in motion, suddenly had a poster child. The message was clear: our violence is order; theirs is threat.

That logic persists.

In 2023, a six-year-old Palestinian-American boy named Wadea Al-Fayoume was stabbed 26 times by his landlord in Illinois. It was a hate crime, spurred by the latest escalation in Gaza. But media coverage was limited. There were no flags at half-mast. No candlelight vigils from elected officials. His life, it seemed, didn’t meet the threshold for national mourning.

In early 2025, Mordechai Brafman opened fire on two Israeli tourists in Miami Beach, assuming they were Palestinians. Seventeen shots. Both men survived. And yet there was no widespread political condemnation, no Sunday show panels, no op-eds framing it as terrorism. Why was that the case? In America’s apparent narrative calculus, that doesn’t compute.

These are not just media failures. They’re examples of what Judith Butler calls “grievable lives,” the idea that some lives are publicly mourned, while others are quietly discarded. It’s not about the facts of the death, but the framework around it.

It’s worth asking: why do some stories get buried?

Groups like AIPAC spent more than $100 million in the 2024 election cycle alone, backing pro-Israel candidates and attacking critics. That kind of money doesn’t just buy influence. It shapes the air. It narrows the range of what’s speakable, and it fosters silence in moments of grave importance.

And yet, even when silence feels safer, questions persist. What are people supposed to do in the face of unrelenting state violence? What is anyone allowed to do?

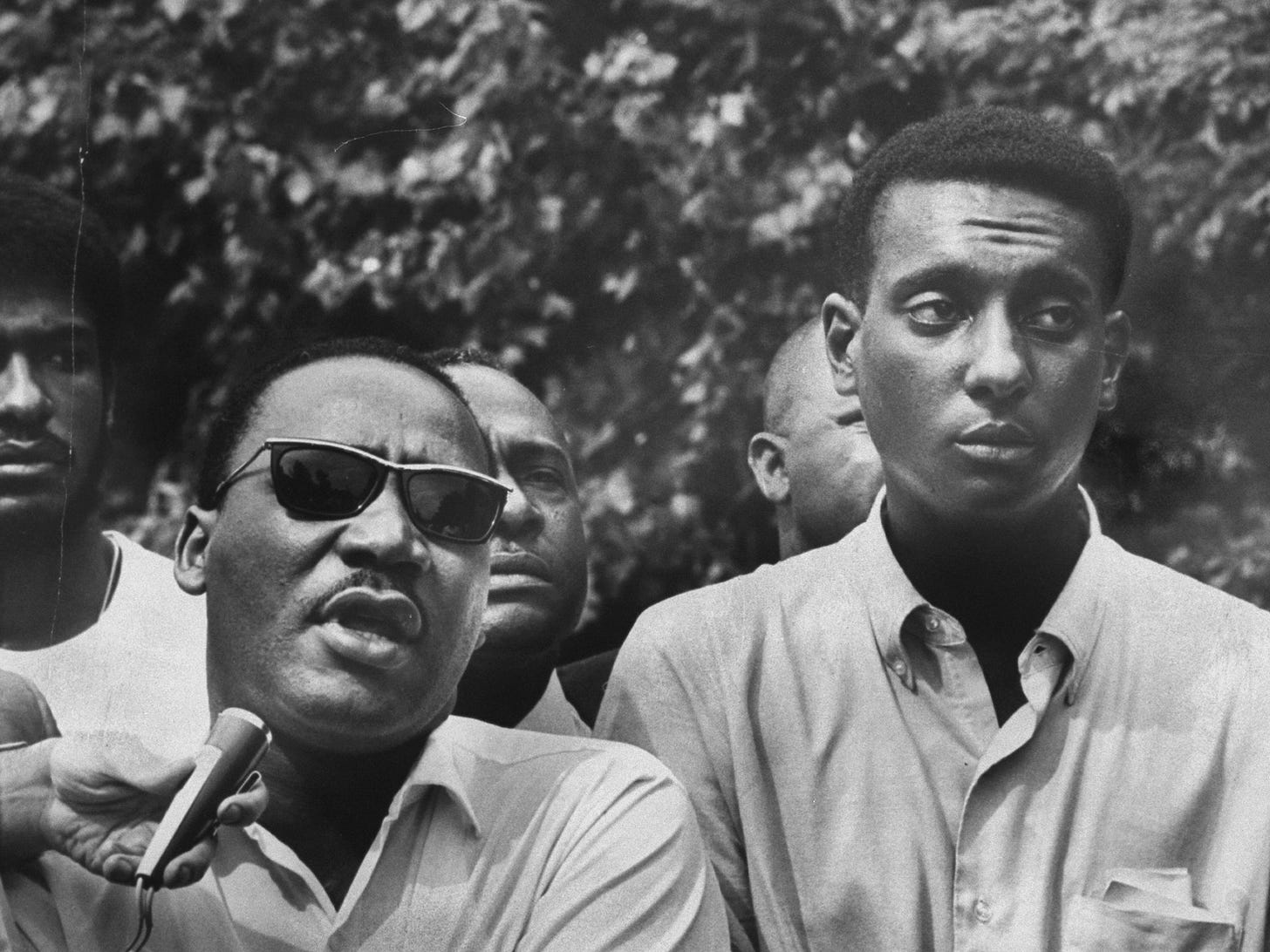

Kwame Ture once asked, “If you were a slave and I was your master, and the only way for you to be free was to strike a blow and kill me, what would you do?” This was a response to another question about the use of political violence. Your own answer is worth pondering.

Maybe the reason this argument makes our ears perk up—why we bristle or flinch or feel the need to look away—is because it implicates us. We are not neutral. As Peter Singer once argued, if you were morally obligated to ruin your new shoes to save a drowning child in front of you, why not send the same money to save a child dying far away? The point wasn’t just about charity, it was about moral distance. The idea that we extend care only so far, and that beyond a certain radius, suffering becomes tolerable. Political violence challenges that radius. It collapses the illusion that we are separate from the systems we live inside, that we get to mourn some deaths and rationalize others.

Liberals often get squeamish around moral ambiguity. They want good people to be good all the way down and evil to be photogenic, obvious. But as Larry David recently wrote in his satirical piece My Dinner With Adolf, even monsters can be charming. They can have perfect skin, a great laugh. They can host dinner parties. That’s part of the danger.

This essay isn’t meant to be comfortable. It’s not an endorsement of anything. It’s a refusal to pretend this world isn’t already soaked in violence. Some lives, no matter how bureaucratic, help sustain it.

I’m not writing this to separate myself from anyone else. I am a citizen of the United States. I benefit from it. I pay taxes that fund bombs. I eat strawberries in January. My carbon footprint is probably ten, twenty times that of someone in a country we call “developing.” Even people with the most progressive ideals—healthcare for all, housing as a right—are tangled up in systems of harm. There’s no clean place to stand. That’s not an excuse; it’s just the condition we live in.

I can’t say who deserves to die. But I know this: some deaths are treated as tragedies, others as statistics. What we call justice depends entirely on which one you get to be.

“But this is what happens when grief and propaganda get woven together: it becomes heresy to suggest cause and effect.”

A fucking banger read.

This was a really great piece. I think that a glorification of non-violence is sometimes naïve when genocide and war completely shift the moral goalposts. But I think I still hold on to some childhood teachings; "eye for an eye and the whole world goes blind". I don't think boodthirstiness leads to justice. Then again, what even is justice in genocide? Justice has already been warped and broken. Retaliatory violence from the oppressed will be turned into justification for the oppressor. But the oppressor will turn anything into justification, and retaliatory violence is inevitable in history. I could go back and forth with myself. I like your thoughts here and the care and respect you always write with.