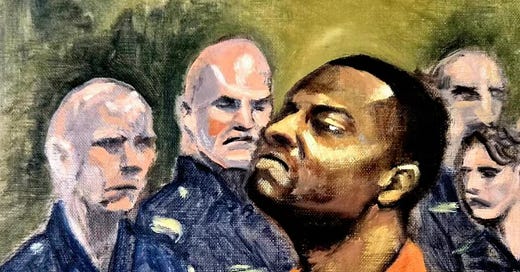

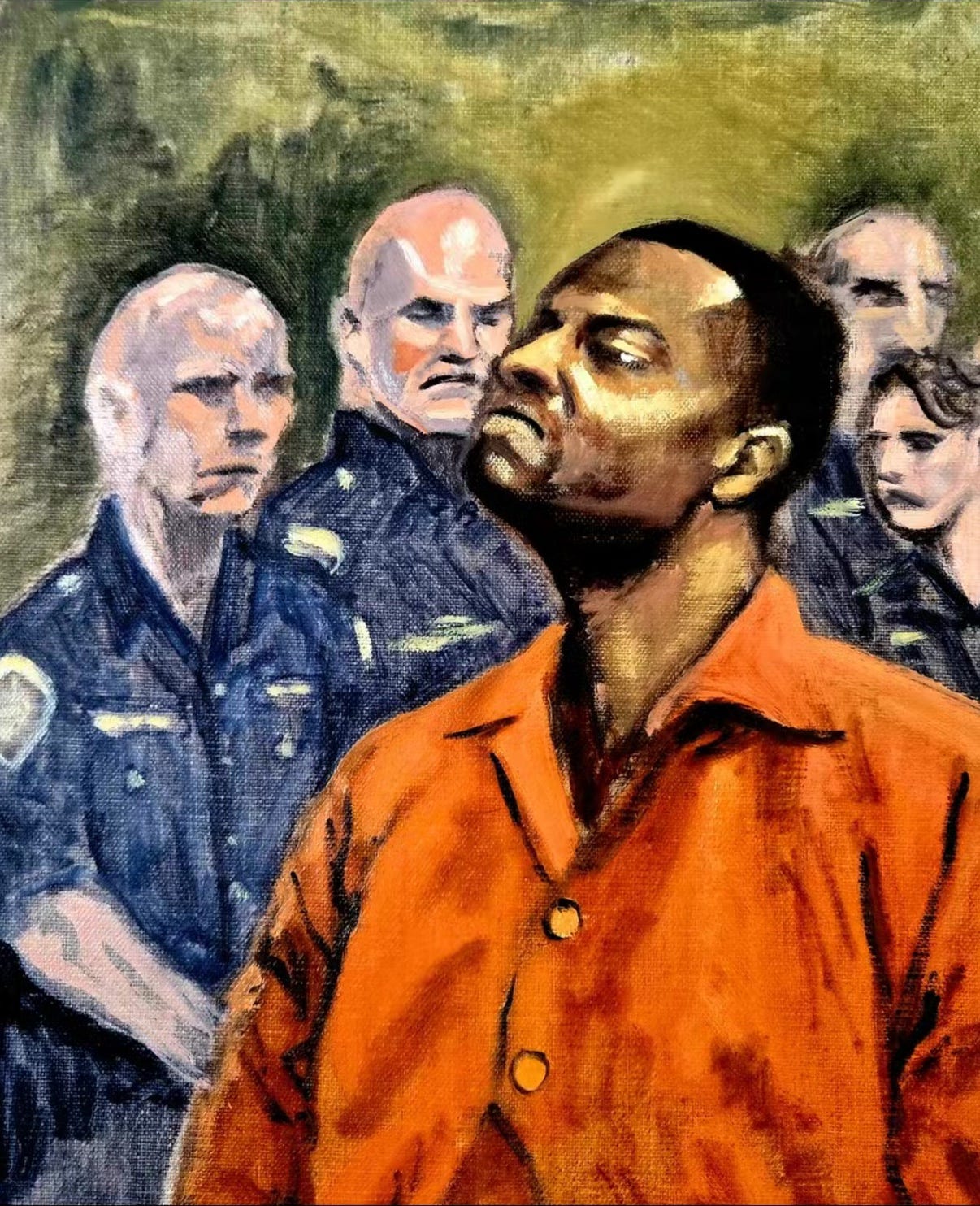

Last week, Rodney Hinton Jr. was indicted for the killing of a cop in Cincinnati. Headlines said he “ambushed” the deputy. They didn’t say he had just watched a video of his eighteen-year-old son being shot to death by police. They didn’t say he’d been spiraling, lost in grief, wrestling with what it means to live in a country where his child’s life could be extinguished and filed away.

Hinton walked out of the station after watching the last moments of his son’s life on video. Six seconds. That’s how long it took from the moment Ryan Hinton and three others fled a stolen car to when police opened fire. Six seconds is the length of a deep breath. A brief hesitation. A pause in a conversation. In that time, officers shouted, “He’s got a gun!” and Ryan was shot dead behind a pair of dumpsters. There was no trial, no negotiation. Just six seconds, and then nothing.

Police know to say “gun.” It’s a word that turns fear into justification. “He’s got a gun! He’s got a gun!” That phrase has become a ritual incantation, used to absolve, to preempt, to frame the narrative before the dust even settles. Whether or not a weapon is actually there often becomes irrelevant, the invocation is what matters. It's the signal to shoot, and the shield when they do.

This isn’t incidental, it’s trained. In police academies across the country, officers are taught to prioritize “command presence” and to default to statements that establish a threat, especially in high-stress chases. Saying “gun” not only justifies force in the moment, it also sets the stage for legal protection afterward. It’s not about truth; it’s about the appearance of fear.

We’ve seen this before. Tamir Rice was carrying a toy. Stephon Clark had a cellphone. Amadou Diallo was reaching for his wallet. The words “he’s got a gun” have preceded countless state-sanctioned killings that later unraveled under scrutiny. By the time the facts emerge the damage is done, and the system has already written its closing argument.

Hinton’s lawyer, in a statement, said:

“Mr. Hinton experienced a psychiatric episode, triggered by watching a video of his son being shot to death. And that because of his mental defect, he did not know the wrongfulness of his conduct when he engaged Deputy Henderson.”

We are not supposed to say it. But I’m not sad a cop died. I’m sad that a man who lost his child to the state’s violence had nowhere to place his rage but back into the very system that took everything from him.

We are told to mourn cleanly. We are told to believe reform is possible. But Rodney Hinton’s story—and the last hundred years of American policing—tell us otherwise.

As historian Elizabeth Hinton writes in From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime and America on Fire, every time public outrage over police violence reaches a boiling point, the country responds with another round of "reform." A new commission is formed. A new acronym is created. Another bill is named after someone who’s already dead. And always, policing emerges more powerful.

Mariame Kaba writes in No More Police:

"Further charges of corruption and patronage ushered in the 'Reform Era' of policing in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In response, reformers sought to professionalize police by adopting new policies and improving selection, training, and management of police departments. The federal Wickersham Commission was convened in 1929 to study the enforcement of Prohibition. Commissioners offered a scathing indictment of police departments across the country, including evidence of brutal interactions and widespread financial corruption. Their recommendations? More reform, more professionalization, better leadership and management, more effective recruitment and training, more legislation, and greater use of science and technology.

Starting to sound familiar? The same solutions are offered a century later."

The same failed blueprint is still being used in 2025.

Policing in the United States has not been meaningfully changed by reform because it cannot be. The institution is functioning exactly as designed: to surveil, control, and kill, especially in Black and poor communities. The results we see aren’t a failure; they’re the whole point.

Over 1,300 people were killed by police in 2024, the deadliest year on record. In 2025, we're already over 400 people. Black Americans are more than three times more likely than white Americans to be killed by police, even though they're less likely to be armed. All over the United States and in our largest cities, the police are found to be abusive and corrupt. In Los Angeles, a federal investigation revealed that over a dozen deputies were part of tattooed deputy gangs within the LASD, linked to harassment and unlawful killings. In 2019, the Plain View Project uncovered thousands of racist and violent Facebook posts by active-duty and former police officers across the U.S. There was virtually no accountability. In Philadelphia, 72 officers were placed on administrative duty, and at least 13 were slated for termination. However, these officers were reinstated through arbitration, and the city paid over $770,000 in back pay to three of them. Despite nationwide calls to defund the police after George Floyd’s murder, no major department’s budget was meaningfully cut. In New York City, by 2023, the NYPD's operating budget was proposed at $5.49 billion, with additional costs bringing the total to over $11 billion when including pensions and fringe benefits. This is more than the entire military budget of most countries on the planet.

Does any of this feel like accountability?

I also have my own personal relationship with the abuse of the police. I was a public defender for four years and spent time dealing with the cops through my clients and their cases.

Cops like Weldon Drayton.

Drayton was arrested for arson while serving as both a Suffolk County cop and a volunteer firefighter, accused of setting buildings on fire and then helping put them out. But his record goes back much further. According to a Newsday investigation, Drayton joined the Suffolk County Police Department in 2010, after serving in the New York Police Department for three years. While in the NYPD, he was the subject of six civilian complaints containing 16 allegations, according to New York Civilian Complaint Review Board records.

In 2014, Drayton—then a member of the department’s Highway Patrol drunk-driving unit—got behind the wheel of his Volkswagen while off-duty, with a fellow firefighter in the passenger seat. While speeding, Drayton blew through a residential street and smashed into Julius Scott’s Honda, pushing the car into a pole. The impact forced Scott into the back seat, peeling the skin from the top of his head and trapping him in the wreckage. He was just one block from home.

Drayton refused a field breath test and the Suffolk County Police Department ignored normal procedure to protect him from taking one, going as far as taking him off scene. After ignoring this procedure to protect one of their own, what was his ultimate punishment? A $150 ticket and the loss of four sick days. That’s it.

Scott, who still suffers from frequent headaches, throbbing pain, and daily back spasms years later, only learned about the internal affairs outcome when Newsday called him years later.

“My life was worth four sick days?” he asked.

This didn’t stop them from keeping him on the job—and it certainly didn’t stop future investigations. It wasn’t until he was alleged to have been setting fires that Suffolk County finally took action. Not for the brutality, not for the irresponsibility, not for the crash that upended a young man’s life. For the optics.

The arson charges were ultimately dismissed.

We are no longer at the place where we can pretend the system can be fixed. We’ve tried the task forces. The community review boards. The body cameras. And each time, policing emerges not weakened, but reinforced—its violence repackaged as necessity, its power expanded by reformist good intentions.

As Michel Foucault observed, reform doesn't dismantle power. It fortifies it. The apparatus of reform does not correct the system, he writes, it re-legitimizes it. The same applies to policing. Reforms that tinker around the edges don’t just fail, they entrench. Rather than keep us all safer, they build a better cage.

We must refocus our efforts, not on reforms that reify a violent system, but on removing its power altogether. We must defund the police. We must divest from punishment and invest in care. We must build something new. To do anything less is to ignore the problem.

People like to say it’s just “a few bad apples,” that not all cops are bad. The irony is that the actual phrase is, “a few bad apples spoil the bunch.” This bunch is rotten. There are cops who lie, brutalize, and kill. Then there are the ones who stand by and watch. They do nothing, say nothing, because they don’t want to disturb their pension. That silence is complicity. That’s not a few, that’s the system.

As Elsa Dorlin writes in Self-Defense: A Philosophy of Violence, self-defense is not only about survival but about reclaiming agency in a world that makes certain people disposable. Have these communities not been made disposable?

Rodney Hinton wasn’t plotting political revenge. He was grieving. He was enraged. And rightfully so.

But was he not also defending himself? His family? His community?

Was Rodney Hinton a hero? I can’t answer that perfectly. I do know he was a father, reacting. Could you watch a loved one be murdered and not react? He spent his life watching police do the things police do, which includes killing boys like his son.

Was Rodney Hinton a hero? I don’t know.

But was he wrong?

Ryan Hinton, April 19, 2007 - May 1, 2025

Not going to be tolerating racist nonsense in this comment section. Have already had to block people.

ACAB

Fuck the police 😤