I flew down to Florida to visit my father for his 80th birthday.

The background noise of the trip, the thing I tried to ignore but he seemed keenly aware of, was his age. I am much more aware of it now. The long scars on both his knees from surgery, his difficulty sitting and standing, his shoulder, which now juts out at a strange angle after a bad fall off his bike that nearly killed him. The slow realization, one that took my entire life and nearly 80 years of his, that he wasn't invincible, and he wouldn’t live forever. Over the weekend he was reading Escape from Freedom by Erich Fromm, a book he insists I recommended to him (which I have no recollection of, though we both share a terrible memory for these kinds of things) and when he reached the last twelve pages, he closed the book and said he was tired of it. He didn’t want to finish.

I resisted the urge to find some deeper meaning in that.

He and my step-mother live in West Palm Beach, inside one of those creepy, gated communities where everything is perfect: lawns trimmed down to military precision, palm trees lined up equidistant along the pothole-less road, small garages built just for golf carts attached to every driveway. The only people not speaking English are the landscapers who toil under the sun, pruning palm trees on the golf course that nobody seems to use. Pickleball, a fascist enterprise if there ever was one, seems to be the real local religion.

We went out to the "fancy" restaurant at the “club” they are loosely affiliated with on our first night. They had a dress code, which set off a fifteen-minute argument about my refusal to wear a long sleeve shirt.

It was 80 degrees. I was sweating through my clothes already. I have gained weight, and the thought of jamming myself into a tucked-in shirt made me want to commit a minor act of terrorism. We circled each other the way we always do, neither one of us wanting to lose, both pretending it was funny.

Eventually I showed up in a wrinkled short sleeve button-down. He muttered something under his breath as we got seated.

The restaurant itself was evil in its own right.

The menus, anticipating the cataracts of a mostly 65-and-up crowd, were lit up with fluorescent panels that burned your eyelids under the dim, fake-candle glow of the room. Each table was weighed down with an absurd number of glasses, a full fleet of wine and water and cocktail options, enough glassware to supply a small army. It looked like a dinner service for people who had forgotten how to eat.

I had come to Florida looking for something just as ridiculous: a clean answer, a neat explanation for all the ways I still come up short. I thought if I asked the right questions, pressed hard enough, I would walk away with something clear. Something that could explain the gaps in me.

I wanted a patsy.

I wanted to believe that the things I struggle with — detachment, guilt, a love that burns bright and then slips through my fingers — were passed down like a fucked-up heirloom. Epigenetic trauma is the concept that extreme experiences like war, famine, or violence can leave chemical scars on your DNA that echo across generations. The idea that you can inherit the smoke of a fire you never even saw. This is what I was looking for.

We sat for a while talking. We walked around the Twilight Zone-esque community and talked some more. He told me about his life before I was born. The marriages, the mistakes, the long, slow slide into bad decisions that colored the earlier half of his life.

He spoke plainly. Sometimes he laughed, sometimes he rubbed his arm and looked off into the distance to think if what he was saying made sense, or felt true. I interrupted less than I usually do.

At some point, as he was describing the slow collapse of his first marriage, the way he drifted in and out of relationships after, the way he stumbled into my mother without a plan, I realized I wasn’t hearing anything new. I had heard all of it before, in fragments over the years.

But this time, I was listening for evidence. I wasn’t just sitting there, letting the story wash over me. People don’t totally realize, when they have a young kid and things with their partner blow up, the primary collateral damage is done to the kid. Even if you do your best, it still ends up that a five-year-old is managing two adult’s emotions and taking on entirely too much.

But what kept coming back to me as we spoke was how much it sounded like the way I move through my own life.

The loneliness. The self-delusion. The walking straight into something I should have known better than to walk into, and pretending afterward that I didn’t see it coming.

It’s easy to pretend you just ended up somewhere.

It’s harder to admit you made a hundred small choices that walked you there, step by step. You didn’t just get here; you drove, you walked up to the door, you let yourself in. The older I get, the harder it is to pretend otherwise. I look at the ways I have hurt people, and not through cruelty, but through carelessness. I see myself more clearly than I want to. And I see aspects of him. Not a villain, not even a cautionary tale. Just a man who made a few bad choices sometimes, and who lived long enough to see the outcome.

I specifically avoid delving into this stuff with both of my parents because it’s a particularly painful thing for me to explore. They are also two people with two very different outlooks and experiences of what happened back then, not to mention my own experience of it that I only half-remember because I was a young child or, for the first few years, not conscious of what was happening around me. But I still have my own thoughts.

More recently, I have wanted the story to be simpler. I wanted him to have been a fuck up, not unlike how I feel about myself. I wanted it to be clean. Certainly, the version of events you hear from “the dad who left,” is not where you expect to hear the story of the good guy.

That story is relatively simple and straightforward. The man runs. The man tries to make up for it, but never really can. It’s the kind of story you hear all the time, the kind of story where you know who to root for and who to blame.

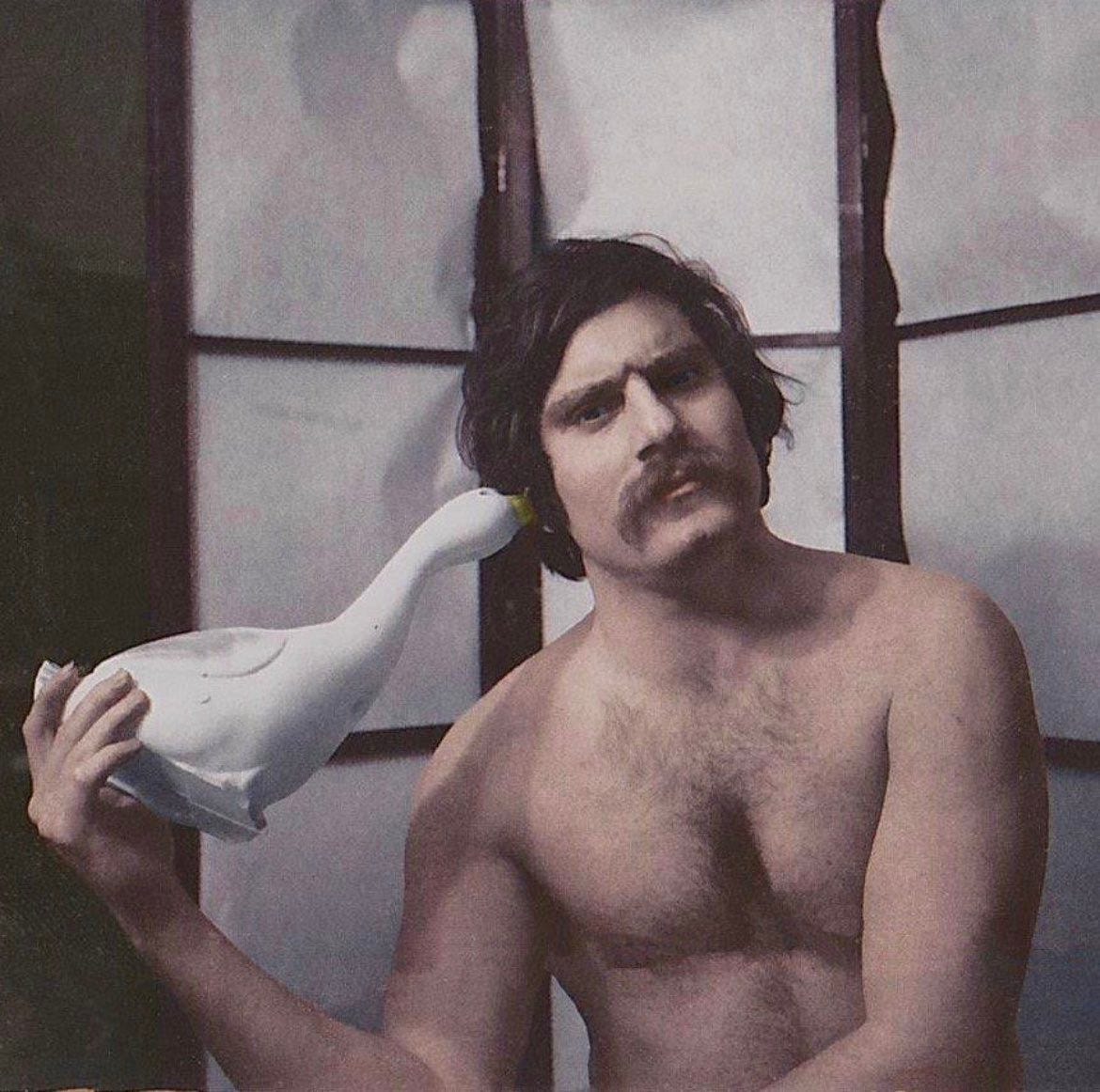

But sitting across from him, listening to him talk about those years, it didn’t feel clean. He certainly wasn’t malicious. At the time he was living alone, was lonely, stupid, stubborn, afraid. He certainly wasn’t a villain. My sisters, all teenagers in the 80s, adored my father and still do to this day. Their own dad, who was by all accounts an alcoholic and for most of their lives a deadbeat, was not someone they could feel a connection with. My dad brought, for a short period, a real light into their lives. My oldest sister, now in her late 40s, will still talk about how my dad took her to Disney World. She loves him.

He was just a person navigating his life with some bumps along the way. The more I thought about it, the harder it was to pretend I was any different. I don’t move through the world with malice either (depending, of course, on who you ask). But obviously that doesn't mean people haven't gotten hurt. I don’t set out to be careless. But that doesn’t change the fact that sometimes I am.

It’s easy to forget, when you’re reading the story backwards, how messy it felt at the time. How good intentions and bad choices get tangled together so tightly you can’t tell which is which anymore. But real life isn’t lived on paper. Real life is showing up. It’s sending your child support, it’s making awkward phone calls and having hard conversations. It’s driving to birthday parties where you feel like an intruder, where you know you are the villain in someone else's story and you go anyway.

Real life is standing there while your four-year-old son, the one you weren’t ready for, the one you thought you didn’t want, runs into another room to get away from you. And following him in anyway. And trying again.

Real life is messier than the easy stories we tell about it.

The people who know him best still love him. My sisters still adore him. Even my mother, who had some right to dislike him, still asks after him. Still tells me to wish him well. If he were the villain, how do you explain that? Maybe they are all wrong? Maybe they are too soft. Maybe they are remembering selectively. Or maybe I am. Or, maybe seeing him clearly, really seeing him, means letting go of the idea that people are only one thing.

I am certainly not innocent. I think about the people I have dated. People who deserved better than being left hanging in the gray zone of my uncertainty.

I told myself I was being honest. I told myself I was telling them the truth. And mostly, I was. I said I wasn’t ready. I sometimes said it kindly, even. But still, some part of me hoped they would wait anyway. Some part of me liked being loved even when I wasn’t ready to love back. It is easy to say you didn’t promise anything. It is harder to live with the reality of the hurt you caused anyway. It is harder to admit that kindness can still leave bruises.

When my dad said, "I wasn't looking for trouble, I just walked into it," I knew exactly what he meant.

I wasn’t looking for trouble either. I just opened the door. Perhaps, in some cases, I stayed longer than I should have. In the end, it’s not enough to say you meant well. Meaning well doesn’t undo the damage; it doesn’t make it disappear.

That is the thing nobody tells you when you are young: you are responsible for the damage, whether you meant it or not. At some point, you have to stop pretending you were just along for the ride. At some point, you have to admit that you were driving.

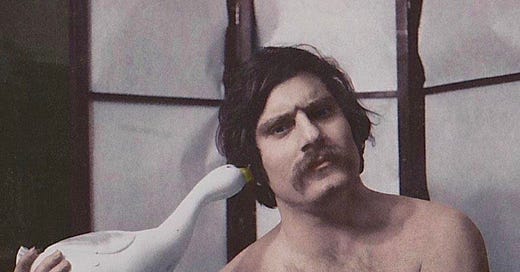

I wanted it to be epigenetic. I wanted to believe I had inherited some broken code, that my father's mistakes had stamped themselves into my DNA. The truth was duller and harder. By his own account, he was not a heartbreaker or a ladies' man. He was lonely and at times awkward. He walked into the wrong situations because he did not know how not to.

My father is 80 years old.

I love him dearly.

He has been one of the most important and influential people in my life. Without his presence, I am not sure who I would be. He gave me so much of myself: my sense of humor, my relentless curiosity, my unwillingness to settle for easy answers. He pushed me to an impossible standard I will never fully live up to, but it is impossible to deny the results.

His sons are both Ivy League educated; one is a talented Broadway actor and musician. The other is, for better or worse, a somewhat known young lawyer. It is not nothing. And it is in no small part because of him.

A successful, loving marriage. Two nice dogs. Two abandoned cats, who I ended up taking care of, who lived out their lives fat and well-loved. Two adoring sons who, for their entire lives, wanted their father’s approval. The gratitude of countless patients, who would sometimes come up to us at Yankee games and in grocery stores just to tell us what a great guy our dad was. Not so bad.

Taking responsibility for yourself is letting go of the idea that someone else made you who you are. Because of course they did. But so did you.

There is no epigenetic fuckboy.

It is me.

It is not me.

It is him.

It is not him.

It is all the unfinished work of loving and being loved.

every time I read one of your newsletters, I think about what a talented writer you are. I'll definitely upgrade when my financial situation allows me to, but for now just wanted to say that I appreciate all of your work!

Wow this really hit. “The man leaves”, and “collateral”. As a child of divorced parents, It honestly made me afraid to date or get serious with anyone, I have become hyper-independent. There’s a part of me that still wishes despite everything more answers.